People always ask us if they qualify for Italian dual citizenship. Luckily, if you have at least one Italian-born ancestor, you probably do! Truthfully, Italian law is very generous towards those with “roots in the boot.” There are many paths to putting an Italian passport in your hands. However, in order to figure out if you’re eligible you do need to know some basic info about your family so be prepared to bring out your family tree.

In most cases you can tell if you qualify for Italian dual citizenship immediately. For others, the path is not as simple. There are many instances where someone can fall under a special category or where further examination is necessary. That’s why we—the experts—have written this brief guide.

In this post, we’ll discuss the most popular paths to qualifying for Italian dual citizenship. We’ll also share 5 rules to figure out if you’re eligible. And as always, if you need extra help, feel free to contact us privately with your questions.

Why are Italy’s citizenship laws so generous?

(For the purposes of this post, we’ll be discussing Italian (dual) citizenship by descent. It is also known as Italian citizenship jure sanguinis and Italian citizenship via heritage.)

To understand how Italian citizenship by descent works, let’s first examine Italy’s history.

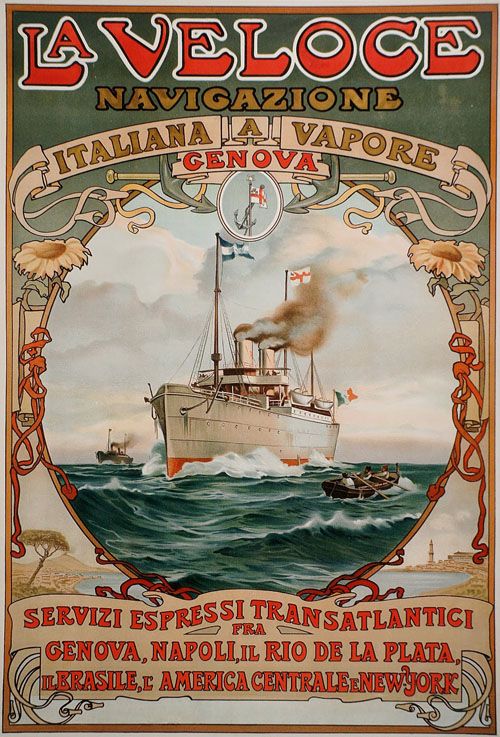

Many years ago Italians left their homeland en masse for other countries in Europe, the Americas, and places beyond. In search of a better life, they established themselves in their new countries and became part of the local communities over time. It is said that by 1920, more than 4 million Italians had emigrated to the United States, representing more than 10% of America’s foreign-born population.

But why did they leave in the first place? For numerous reasons.

By the late 1800s (1861, to be exact) Italy had finally become a unified nation, but the land and people were by no means united. Decades of infighting, social chaos, and violence along with natural disasters and disease left many Italians in abject poverty. Peasants living in the mostly rural, poor south had little means of improving their lives. The newly formed Italian government had little means of helping its citizens, so people looked elsewhere for opportunities. As transatlantic voyages became more affordable—and as word of America being the “land of milk and honey” spread—many Italians heeded the call of “L’America.”

The Northern vs. Southern Divide

America’s first small wave of Italian immigrants came from the North. They were primarily artisans and shopkeepers seeking a new public to which they could sell their wares. Later on came the much larger wave of Italians from Southern Italy. Unlike their Northern Italian counterparts, these immigrants were mostly farmers and laborers looking for work—any work. A significant number of these immigrants were single men; many of them stayed for a short time. Within five years, between 30% and 50% of these immigrants would return home.

Those who stayed in America usually retained close contact with family back home. They also sent remittances: in 1896 an Italian commission on immigration estimated that immigrants sent home between $4,000,000 and $30,000,000 a year, and that the “marked increase in the wealth of certain sections of Italy can be traced directly to the money earned in the United States.”

What this means for Italian citizenship law

While these remittances certainly helped, Italy continued to struggle due to a loss of manpower, revenue, and taxes.

However, there was a solution. Italian law would determine that anyone descended from a qualifying Italian citizen would also be Italian even if born abroad. This allowed people of Italian descent to maintain close legal, political, economic, and social ties with Italy… an opportunity that still exists today for those seeking recognition of Italian citizenship by descent.

Perhaps unique in the world, Italy still allows people of Italian descent to claim citizenship no matter how many generations have passed between them and their last Italian-born ancestor.

What’s more, the rules of eligibility themselves are quite generous. Therefore, if you are wondering whether you qualify for Italian dual citizenship, the answer is most likely “yes.”

If you qualify, you’re already an Italian dual citizen

A lot of people think that if you qualify for Italian dual citizenship, then you’re “applying” for it. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

If you are eligible, you’ve actually been born Italian and have been a citizen your entire life! Think of it this way: your citizenship is lying dormant, just waiting for you to have it legally recognized.

For that reason we’ll refer to it as claiming your Italian citizenship rather than applying for it.

Italian dual citizenship is like a chain: one broken link and you no longer qualify

Did we already mention that Italian citizenship law is generous? Well, it really is. A person can qualify for Italian dual citizenship no matter how long ago your last Italian-born ancestor left Italy. You also don’t need to speak Italian, live in Italy (unless you want to), be 100% Italian (or even 50% or 25 % Italian), have an Italian name, or any other arbitrary benchmarks of Italian-ness.

You simply have to qualify. To do this, the chain of Italian citizenship in your family must be unbroken. Here’s what we mean:

It helps to think of Italian citizenship as a chain and each single link as a person in your family. For you to qualify, each link must be intact… and each person in your family must either be an Italian citizen or qualify for Italian dual citizenship before you.

The general principle of Italian citizenship by descent

A link is only broken when Italian citizenship is lost. Before August 15, 1992, any Italian citizen could lose citizenship automatically if he or she became a citizen of another country.

This means that if your ancestor lost Italian citizenship (by becoming American or via other means), then that link is broken and every person born after the loss of Italian citizenship no longer qualifies.

This is the general, overarching rule of how to qualify for Italian dual citizenship. However, there are specific criteria you must also meet.

5 steps to qualify for Italian dual citizenship

Follow these 5 foolproof steps to see if you qualify.

- Find your last Italian-born ancestor. If you have more than one, repeat this process until you qualify.

- Determine when your ancestor was alive. If after March 17, 1861, continue. This is the date Italy became a modern country. Before then, there was no Italy. And no Italy means no Italians… which means no ability to pass on Italian citizenship. That’s why your ancestor must have been alive after this date.

- Did your ancestor ever become an American citizen? If both after July 1, 1912 and after the birth of his or her U.S.-born child, continue.

- If your ancestor never became an American citizen, congrats. You automatically qualify!

- Finally, are there any women in your direct line of Italian descent? As long as each woman had her child on or after January 1, 1948, you can qualify through the “normal” channels. Otherwise, read up on the loophole section below.

Practical examples

[su_icon_text color=”#000000″ icon=”icon: group” icon_color=”#13ef85″ icon_size=”31″]Giovanni, an Italian citizen, was born in Rome in 1920. He came to the US in 1950 and had a son, Mark. Giovanni then became an American citizen in 1952. In 1954, he had a daughter named Joanne. Because Mark was born when his dad was still an Italian citizen, he (Mark) was born an Italian dual citizen. Both he and his spouse and his children can became recognized Italian citizens. Joanne, on the other hand, cannot. She was born after her dad became American and thus, the chain was broken. She will have to find another way to qualify. [/su_icon_text]

[su_icon_text color=”#000000″ icon=”icon: group” icon_color=”#ef3113″ icon_size=”31″]Amanda was born in NYC in 1989. Her mom, Celia, was born in NYC 1959. Celia’s dad Franco was born in NYC in 1920. Franco’s dad Antonio was born in Italy in 1890. Antonio never became a US citizen. Because of this, Franco was born a dual US-Italian citizen. So was Celia, and so was Amanda. Franco, Celia, and Amanda (along with their spouses and children) can seek recognition of Italian citizenship by descent.[/su_icon_text]

The loopholes

1948 Cases

Throughout Italian history the law has heavily discriminated against women. In fact, before January 1, 1948 (the date of Italy’s modern constitution) women could not pass on citizenship to their children except under very explicit circumstances such as:

- When the children’s father was unknown; and

- When the children’s (foreign) father’s own citizenship could not be passed down due to the laws of his country at the time;

- Other specific (and rare) circumstances.

Therefore, even if you meet all other criteria but descend from an Italian woman whose child was born before January 1, 1948, people with a basic understanding of Italian dual citizenship (including Italian consular workers) will say you don’t qualify. This is not correct. Since 2009, thousands and thousands of people have successfully claimed their Italian citizenship even with pre-1948 maternal ancestry.

How?

They took it to court. These people are known as “1948 cases” and must hire an Italian attorney to represent them in court. Attorneys have successfully argued that this law is discriminatory and won recognition of Italian citizenship for many. As a rule, 1948 cases have a high degree of success. Therefore, if you are a 1948 case you can still obtain Italian citizenship, you will need to hire an attorney. We can help with this! More info here.

Pre-April 27, 1982 Marriages to Italian Men

Here’s another fun loophole you might qualify through.

Before April 27, 1983, any foreign woman marrying an Italian man would automatically become an Italian citizen on the date of marriage. And since Italian law states that people who qualify for Italian citizenship jure sanguinis are in essence Italian citizens from birth, this means that women marrying men eligible for Italian dual citizenship become Italian, too!

Here’s an example:

Melissa married Johnny in California on April 10, 1979. Johnny’s dad was born in Italy and was still an Italian citizen at the time of Johnny’s birth. Since Italian law recognizes Johnny as a citizen since birth (Johnny just hasn’t sought formal recognition of that status yet), Melissa, too, became an Italian citizen on April 10, 1979. If Johnny requests formal recognition of his citizenship, Melissa’s own citizenship will fall under the umbrella of Johnny’s and they’ll both become recognized Italians at the same time.

Cool, right?

We see these cases a lot. Oftentimes people will think they don’t qualify because their male Italian ancestor lost Italian citizenship before having a child. However, if that male Italian ancestor married a woman before April 27, 1983 and was still an Italian citizen when that marriage occurred, then this loophole is valid!

Putting it all together: how to actually seek recognition of citizenship

So, you know you’re eligible, you want Italian citizenship, and you’re ready to seek recognition. Here’s what you need to do.

- Gather the documents you need. Each Italian consulate in the US has its own rules (because why would anything Italian ever be uncomplicated?). This means they all require slightly different documents. The idea here is that you will reconstruct your family tree through certified copies of vital records. This can include birth, death, marriage, and other records.

- Translate your documents into Italian. And trust us, hire a pro. You want someone who has translated these types of records before.

- Go to your appointment. Or apply in Italy. It’s up to you!

- Await recognition.

- Register in AIRE (the Registry of Italians Living Abroad) if you are living outside Italy. Then, apply for a passport.

- Enjoy your citizenship!